Home Economics, Haven or Exile for Women Scientists?

Women’s scientific aptitude was acceptable when applied to food, child-care, or cleaning.

Home Economics students at Cornell University building furniture in 1944.

Read about the early history of women’s education in the United States here: More than you think, but still not enough .

Believe it or not, Home Economics was a common college major for women in American universities until the 1970s. Since the 1970s, Home Economics has gained a reputation of being anti-feminist, and has frequently rebranded itself as “Life Skills’, “Human Ecology”, or other generic names. The history of Home Economics departments and the feminist analysis of this history has shifted quite a bit in the past several decades. In the 1990s, many feminist science scholars argued that Home Economics departments were refuges for women scientists. They provided women scientists unprecedented opportunity to conduct original research, obtain science degrees, and find employment opportunities. And that is true. Home Economics was just not about teaching cooking or sewing; Home Economics research pioneered research in child psychology, nutrition, microbiology, and textile science. Curriculums were very heavy in math and science classes. In the United States, we have standardized clothing sizes, nutrition labels, and school lunch programs because of Home Economics research and advocacy. And many women graduates were able to get industry jobs, earn a salary, influence public policy, obtain faculty positions.

However, more recently, as demonstrated in Danielle Dreilinger’s fantastic book “The Secret History of Home Economics”, the legacy of Home Economics is much more complicated. Often, female college students were almost forced to major in Home Economics whether they liked it or not since they were barred from majoring in other STEM fields by university administers or their own families. Home Economics curriculums also encouraged conformity to white-middle class ideals, intentionally or unintentionally crafting the “1950s housewife mythology”. They also had classist, racist, and sexist views about marriage, sex, and domesticity. They were often racist and exclusionary, often failed to relate to the working-class constituents, and made disturbing efforts to support American imperialism and eugenics.

I had no idea about the rich history of Home Economics departments in American colleges and universities until I took a feminist science studies course in college. Its history feels very suppressed in mainstream discourse of Women in Science. Overall, the culture of Home Economics departments was a strange mix of feminist and anti-feminist ideals. However, it was a very scientifically rigorous field of study, and its impact can be felt today. This is the first of many articles I plan to put on the History of Home Economics.

Home Economics Begins

Given the difficulties that many women faced in accessing college in the 19th century, let alone a STEM degree, it is unsurprising that a new field, based on the “domestic sciences” would emerge and fit the bill nicely. Dovetailing with the increasingly vocational aspect of American postsecondary education and the rise of the Land Grant University, it provided women the chance to pursue science degrees in a socially sanctioned way. The field could also provide opportunities for women scientists who were sidelined in their careers.

Courses in “domestic economy” (sometimes referred to as “domestic arts”, or “domestic sciences”) began to appear at newly formed land-grant colleges. These so-called land-grant colleges originated with the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act. They were established with the purpose to “teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the States may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life” [1]. “Domestic economy” courses were a way to meet this requirement, particularly in regard to vocational training for women. Courses related to housekeeping, sewing, food preparation, and nutrition were soon developed [2].

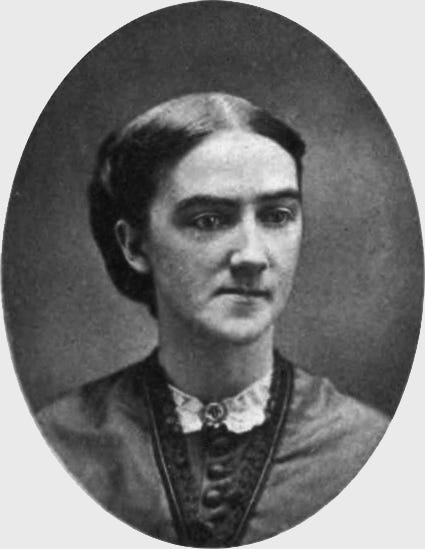

The field of Home Economics started its process of formalization at the Lake Placid conferences (1899-1907), which culminated in the creation of the American Home Economics Association (AHEA) by 1909. Chemist Ellen Richards is regarded as a pivotal leader in the movement. To her, the development of Home Economics was deeply personal. Richards had been denied the opportunity to pursue a Ph.D. despite being the first woman to earn a B.S. at MIT. Instead, she opened a Women’s Laboratory at MIT and began applying her chemistry skills to domestic tasks, such as cleaning and cooking, and then publishing her results. For Richards, Home Economics provided an outlet for her chemistry skills, and as she reasoned, for other women scientists. Her vision was for the field to become established at the elite women’s colleges on the East Coast. Subsequently, she pushed for the incorporation of more science into the field in order for it to be recognized as rigorous [3].

Representatives at the Lake Placid conferences, however, were divided about what the “purpose” of the field should be. Since Stowe’s treatise, the field had been firmly entrenched in the domestic sphere. However, the emerging Progressive Movement in America had brought forth new ideas of social and political reform. Furthermore, women were heavily involved in the Progressive Movement, not least of all in working towards gaining suffrage. As Baker argues, throughout the 19th century, women had been influencing politics through clubs and networks which worked toward “moral reform” that addressed injustices towards women and children, such as lack of employment opportunities or treatment of female prisoners. By the end of the 19th century, these groups aligned themselves with other activist groups to lobby for the passage of legislation [4]. Home Economics could provide yet another opportunity to combat illness, disease, and poverty.

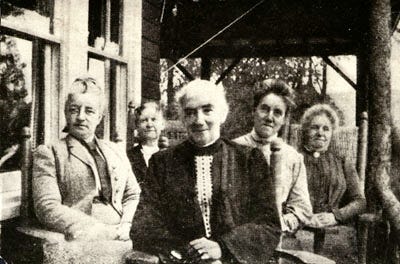

Lake Placid Convention, 1899. Left to right: Annie Dewey, Maria Daniell; Ellen Swallow Richards, Alice Peloubet Norton, Maria Parloa.

Ultimately, the “purpose” of Home Economics came to be associated with three areas: domestic instruction, scientific research, and public advocacy.

The most well-known area was teaching domestic skills and tasks related to family life, such as cooking, sewing, cleaning, and childrearing. The next included conducting scientific research, in areas such as sanitation, nutrition, psychology, food science, and textile science. This research could then be used for the third area, remedying social ills, such as infectious disease, malnutrition, infant mortality, and poverty, through education and outreach in partnership with the federal government. Given these somewhat disparate purposes, one of the most contentious issues at the Lake Placid conferences was the selection of an appropriate name which would define the field. Different members aligned themselves with these different factions. For example, the science faction, led by Ellen Richards, saw the field as a way to provide women scientists with employment in academia and industry). However, the push-pull of these different factions early on eventually contributed to the lack of clear and consistent goals of the field. And though some argued for the inclusion of boys’ participation, the field quickly became sex segregated as well [3].

Parks, G., photographer. (1943) Home Economics students baking bread at Daytona Beach, Florida. Bethune-Cookman College, 1943. Feb. [Photograph]

The Lake Placid Conferences, however, were remarkable in how they worked to get women out of the kitchen. Much of the focus of the first meeting was on ways to improve women’s education by pushing for postsecondary education for women that could lead the new home economics movement [2]. Members of the conference were educated women who worked as teachers, organizers, authors, and lecturers in such areas as cooking and the domestic sciences Members of the Department of Agriculture attended, and were instrumental in hiring graduates, publishing research, and testifying to the scientific soundness of their work. By 1902, the movement encouraged Home Economics to use its principles to improve the general social system, encouraging women to participate in broader social activism [5]. Furthermore, there was an emphasis in pushing scientific principles from the start, most notably by championing germ theory, starting with instruction on the basics of hygiene in primary school and culminating in advanced courses in bacteriology in college and graduate school [6]. Community outreach was another way to instruct others on sanitation, through imparting rules of disease prevention and basic scientific principles, even going as far to encourage housewives to seek access to a microscope. Such efforts were sometimes elitist in their assumptions. The poorest constituents were often unable to access clean water or sanitary toilets [7].

Ultimately, the name “Home Economics” was decided upon and as Stage argues, “The term ‘home economics’ borrowed its perspective from the emerging social sciences and most clearly positioned the home in relation to the larger polity, encouraging reform and municipal housekeeping”. Ultimately, Richards was never happy with the name “Home Economics”. Richards had, in fact, argued for “euthenics”, meaning ‘better living’ which would have emphasized the social and science aspects of the field [2]. And Wilbur O. Atwater of the U.S. Department of Agriculture urged for “home science”. Furthermore, Home Economics never gained the strong foothold in the so-called Seven Sisters colleges as Richards had hoped, but instead became primarily associated with Midwestern land-grant colleges, such as Cornell, Iowa, Illinois, and Chicago, with the enthusiastic support of the Department of Agriculture [3] [8] [9]. In fact, Home Economics received a lot of federal funding and support. Home Economics would play a crucial role in extension work for state-land grant universities in the 1930s and 1940s.

Home Economics faculty at Cornell University going on an extension trip in 1913.

Conclusion

Similar to how women’s college provided opportunities for women scientists, Home Economics Departments within coeducational institutions were the refuge (or exile) for many women scientists. And they worked hard to make the field respected and rigorous.

One of my own great Aunts obtained a college degree in Home Economics in the 1930s. She never married and taught high school and college courses in textile science, eventually becoming an administrator at the high school. It provided a way for her to economically support herself.

Sadly, the culture has not changed much. Many women scientists end up relegated to highly feminized fields such as hygiene, nutrition, life sciences, or food science. Not that these fields are unimportant, but excluding them from other fields limits new ideas and perspectives.

More to come on how Home Economics Rose, Fell, and Declined in the 20th century!!

References

[1] Congress, “Morrill Land Grant Act,” USDA, 1862. https://www.nal.usda.gov/legacy/topics/morrill-land-grant-college-act (accessed Feb. 07, 2022).

[2] E. S. Weigley, “It Might Have Been Euthenics: The Lake Placid Conferences and the Home Economics Movement,” Am. Q., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 79–96, 1974, doi: 10.2307/2711568.

[3] S. Stage and V. B. Vincenti, Eds., Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of a Profession. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997.

[4] P. Baker, “The Domestication of Politics : Women and American Political Society, 1780-1920,” Am. Hist. Rev., vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 620–647, 1984, [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1856119

[5] S. Stage, “Ellen Richards and the Social Significance of the Home Economics Movement,” in Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of the Profession, S. Stage and V. B. Vincenti, Eds. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997, pp. 17–33.

[6] “Courses in Bacteriology for Home Economics,” J. Home Econ., vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 627–630, 1910, [Online].

[7] N. Tomes, “Spreading the Germ Theory: Sanitary Science and Home Economics, 1880-1930,” in Rethinking Home Economics: Women and the History of the Profession, S. Stage and V. B. Vincenti, Eds. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997, pp. 34–54.

[8] M. Nerad, The Academic Kitchen: A Social History of Gender Stratification at the University of California, Berkeley. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1999. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books?id=sHspQcJVrjQC&pg=PA21&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false

[9] G. Adams, “Fifty Years of Home Economics Research,” J. Home Econ., vol. 51, pp. 12–18, 1959, [Online]. Available: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924053760306&view=1up&seq=25&skin=2021