My great-Aunt, in her late teens, before she entered a convent. Late 1940s.

A lesser-known subsect of women scientists are Catholic nuns. In the Catholic faith, a nun is a woman who has taken certain vows of devotion. This includes vows of chastity, obedience, and poverty.

My great-Aunt, born in 1929, was very interested in Math and Science as a kid. In high school, she took Calculus and was the only women in the class! This is remarkable since, today, only about 20% of American students take Calculus in high school.

Unfortunately, the Great Depression and then World War II dominated most of her childhood and teen years. Neither of her parents had graduated from high school, though her father was a voracious reader and provided books for the household. Her parents had married in 1926, when the economy was booming, and their prospects were good. But then, the stock market crashed. They were evicted form a home they had been renting from relatives (a painful memory for my Aunt). Her father worked nearly round the clock at an auto plant and even tried to launch a freelance business to make ends meet. Her mother was overwhelmed, and she and her siblings had a dysfunctional childhood. Then World War II hit, and her father was drafted. They were able to get a deferment and then a second deferment, but there was constant fear that he would be called up. The War Office stated that if he was called up again, that he would have to go, despite having 5 children. My Aunt had a lot of responsibility, taking care of her younger siblings while going to school. Despite all this, she graduated high school in 1947, at a time when only 59% of students did so.

But, there was nothing else for her to do. Their family did not have the money or inclination to finance college. Despite her good grades, her chances for college admittance (even if she could afford it) were not great. As I will detail in later articles, the GI Bill, while providing unprecedented access to higher education for returning (white, male) veterans, also significantly pared back female enrollment which had skyrocketed during the war. During World War II, many women majored in and worked in scientific fields. However, when the war ended, most were laid off, and the “back to the kitchen” movement was in full swing.

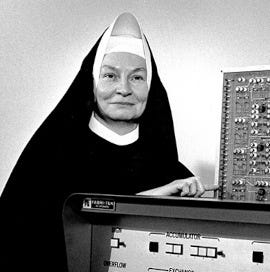

My Aunt in her religious habit.

So, she became a nun. In her words, it was because she “didn’t know what else to do”. She did have a devotion to the Catholic faith, but I’m not sure entering a convent would have been her first choice. However, she had a relative who was also a nun, which may have influenced her. So, she entered a religious order for almost 20 years. They sent her to college, and she taught in Catholic elementary schools. Every 4-5 years they would move her to a new parish, but her family could still visit her. Her college education allowed her to continue teaching when she left (to marry a priest in the late 1960s) and to earn enough money to support herself and retire.

Catholic Nuns in STEM

As Margeret Rossiter uncovered in her Women Scientists in America trilogy, professors at American Catholic Universities were sometimes nuns, even as far back as the 1920s. The first, Sister Angela Dorety, was a professor of botany in the College of St. Elizabeth’s in Convent Station, NJ. In fact, she was the first Sister in the U.S. to receive a Ph.D. (1909 University of Chicago). At St. Elizabeth, she directed a botany experimental station.

By 1938, there were at least 31 nuns who were professors at Catholic universities in the U.S. Their fields of instruction included physics, zoology, chemistry, botany, math, medical science, psychology and nutrition. There were no nuns in anthropology, astronomy, engineering, geology, or microbiology because these subjects were rarely taught at Catholic colleges (pp. 143-144 Rossiter). However, their participation in different fields of study continued to expand. For example, Mary Kenneth Keller was the first woman to earn a PhD in computer science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1965. Sister Florence Marie Scott of Seton College, PA, was one of the first sisters ever elected to an office, when she was elected to the board of trustees of the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, MA (p 307 Rossiter). In a tragic case, Sister Dorothy Stang, of Dayton, Ohio, was murdered in 2005 during her advocacy for rainforest preservation.

In the 1960s, The Sister Formation Movement, originating from Rome in the wake of Vatican II, advocated for increased access to graduate-level education for Catholic nuns. In 1961, Reverand Mother M. Regina, R.S.M (Marquette University) established the Sister Formation Graduate Study and Research Foundation to procure and distribute funds for graduate-level study (p74 Rossiter).

There have been other women of science who were nuns outside of the U.S., famously Sister Kenny (Australia) who developed treatments for polio, and Belgian nun Marie Louise Habets who worked as a nurse in the Belgian Congo and coordinated humanitarian relief efforts during World War II (immortalized by Audrey Hepburn in A Nuns’ Story).

List of nuns who were STEM faculty at American Universities, 1950-1970. Source: p209, Rossiter

Struggles of Navigating Science and Religious Orders

There were relatively few, thriving Catholic universities in the United States by 1920. Though they had been established around the county’s founding, they largely had religious intents. In the late 19th century, they began adding other degree programs like business or medicine. During the interwar years, Catholic higher education developed formalized undergraduate programs and established degree-granting women’s colleges. Some female religious orders fought for accreditation of these institutions, expanding the number of Catholic universities in the U.S. Other, more established institutions, like Marquette University, also became co-educational, despite objection from the Vatican. Increased demand for higher education after World War II by returning GIs, incentivized the expansion of staff and course offerings at Catholic universities. The Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965 also increased autonomy of Catholic institutions.

The experiences of Catholic Sisters and their role in science, has been relatively unexplored, for various reasons. Recently, Peggy Delmas, an associate professor of educational leadership at the University of South Alabama, published a qualitative account of early scientific nuns in the United States arguing that:

She revealed that many nuns in science had made serious contributions to research, some even being considered for a Nobel Prize. Sometimes, these women struggled to navigate norms and expectations in male-dominated departments. Delmas reports the experiences of three nuns (“Mary”, “Judith”, “Anne”) who became professors in the 1960s:

There were many advantages that went along with the women’s religious identity. Participants perceived their single, childless state as one advantage of being a Catholic woman religious faculty member in higher education, because they could focus more intently on their professions. Anne’s colleague explained, “They’re able to focus more on their work and not be tied down to worrying about what they’re going to have to eat when they get home or whether their children need them.” Their extensive educations were also viewed as advantages for both Anne and Judith. Anne also cited the “sister companions” her congregation had assigned to live and work alongside her as an advantage because these women shared her life and kept her spirits up during difficult times at work. In Mary’s case, her experience in the male-dominated Catholic Church was seen as an advantage because it prepared her to deal with the male dominated department in which she found herself working at State University; it gave her a “feminist sensibility,” according to a colleague. Additionally, all three women were perceived to have strong value systems and a genuine concern for people, which were advantageous to them in their academic settings. Participants in Anne’s case spoke of the comfort she gave to others as well as her ability to treat the whole patient, including their spiritual needs, when necessary. A student of Anne’s noted “Someone who’s been trained to give spiritual comfort can be just as soothing as any kind of medicine.”

LEFT: Mary Kenneth Keller, the first woman to get a PhD in computer science. She founded the computer science department at Clarke University and helped to establish the Association of Small Computer Users in Education (ASCUE). RIGHT: Screenshot from the 1959 movie “A Nun’s Story”, depicting the Sisters in a microbiology lab.

It wasn’t always easy, though, to pursue higher education within a religious order. Catholic sisters often had to petition superiors for higher educational opportunities and still follow strict religious dictates. A Nun’s Story exemplifies this struggle when the main character leaves the order to aid the Belgian resistance during World War II.

Sister Diana Stano, who had a strong desire to become a medical doctor, was able to negotiate religious life and her educational goals:

Originally wanting to be a doctor, Sister Stano describes herself as a typical young woman before joining the Ursuline order. She worked regular jobs, met a lot of new people and even dated. But shortly after graduating from high school, a former teacher told Sister Stano that she had a "vocation" or a calling to serve the church. That statement hit home with Sister Stano. "I always felt like there was something missing, and I didn't know what it was," she said. Joining the order didn't stop her from achieving her goals. After obtaining her bachelor's degree from Ursuline College, she petitioned the order for permission to attend Ohio State University to get her doctorate in science education. Ohio State also allowed her to skip over her master's degree to obtain her doctorate.

Of course, these women would have to stop and attend religious services, adhere to certain decorum and dress codes while studying at college. In some instances, they were not allowed to casually converse with lay students. Participation in extracurricular activities or other opportunities probably were out of the question. However, given the economically disadvantaged background that many experienced, this may have been their only opportunity to attend college as a young adult.

Of a similar age and social-economic circumstances as my aunt, Sister Mary Jane Masterson, of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Cleveland, wrote a detailed memoir of her life as a nun. She was “recruited” by encouraging nuns during high school and convinced to join a religious order after a particularly enlightening spiritual retreat. She, in fact, went to college and described her experiences:

As our first year in the novitiate ended, I looked forward to beginning college. Canonical year had been tranquil and joy-filled, but, like a fledgling bird, it was time to leave the comfort and security of a cloistered life […] While two or three of my classmates needed to finish high school, those of us who had finished were enrolled in St. John College, located at Cathedral Square in Cleveland, where we would be trained to teach in elementary school, since at the time there was a need for elementary school teachers. Eventually I became a high school teacher, but training in the fundamentals of elementary education and classroom management, techniques, and skills was an invaluable asset in my teaching career. In the 1930s, the college was known as Sisters’ College and was established for nuns only as a teachers’ college. Later, it became St. John’s College, a diocesan women’s college for teachers in elementary education and for nurses. Both laywoman and nuns were enrolled in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Eventually, the college was closed and the building razed. […] When college became a reality, I was overjoyed to enter the world of academia. We were bused to and from college and during the day reported to one or another of our sisters who were professors at the college. At least one professor accompanied us on the bus and we had to report to one of them at a specific time during the day. We had lunch together and were not permitted to fraternize with sisters from other communities or with lay students. The rule puzzled and saddened me, because it would be enriching to know sisters from other communities, as well as laywoman. Fortunately, very few of the lay students were scheduled in our classes, so we were spared the embarrassment of being in class with a laywoman and not speaking to her.

Motivations for joining and leaving convents are harder to assess, and trends in experiences are hard to parse out as many archives are closed to researchers. In some cases, women who were too “outspoken” about Civil Rights, particularly black nuns, were bullied into leaving the order and experienced discrimination. Assault or abuse from superiors could be another reason. In, one case, Jen O’Leary, left her religious order because she had romantic feelings for women and became a gay activist. However, there was often a deep sense of inner turmoil, or judgement from others when leaving a religious order. However, many of these women provided invaluable, unpaid labor and service towards education.

Conclusion

My Aunt in the early 2000s, 30 years after leaving her religious order.

Many women in my Aunt’s family ended up marrying very young and living a life of economic uncertainty and out-right poverty, replicating toxic patterns of previous generations. Through her education and life experience, she was able to support herself and develop a sense of independence and self-reliance. While she never made any scientific discoveries, she developed a life-long love of learning and teaching. In retirement, she was unfortunately widowed. However, she moved to another part of the country, travelled the world, made new friends, ice-skated, gardened, and still regularly calls and writes letters. Long after she retired, my Aunt continued to self-educate by reading books and textbooks and teaching herself French. A woman who wants an education cannot be stopped.

A slight tangent: there's a book about lesbian nuns. It's called 'Immodest Act: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy" - and it gets into the history of how the church viewed women in general, and lesbians specifically. Might be of interest to you, so throwing it out there.

The first nun you mentioned "Sister Angela" was a botanist? This is a loose connection but I couldn't help thinking about 'Suor Angelica', the Puccini play. It's about Sister 'Angelica' who is an herbalist and tends her botanical garden (what?!). She ends up designing a poison to kill herself once she finds out her son is dead (whose birth was the reason she was sent to the convent by her family). Anyway. I just think this connections of the 'Angela/Angelica; names in botany and herbs is wild. Another fascinating post. Your aunt is the coolest.