How many authors have finally completed the manuscript, only to log into the submission portal and see the baffling request for “6 keywords” to describe the paper. Do you pick the 6 most frequent scientific terms that appear in your paper? Or pick unique terms not appearing in your paper to attempt to hack Google’s Scholar’s search algorithm? Or do you just close your eyes and pick?

Does it even matter at all? Yes, it does, it’s often used as a flawed type of archival system for all scientific papers, that can make or break your research paper’s visibility, and hence citation rate.

The Dreaded Keyword: Why They Dictate the Science We See

Keywords indicate the topics (“microbiome”, “genomics”) covered in a scientific paper. Typically limited to around 6, they are created by the authors and submitted with the manuscript. Keywords are then attached to the manuscript. Keywords are very important and serve several purposes:

Discoverability and Visibility: Sorting books and materials by topic has historically been used in bibliometrics, information retrieval, and knowledge organization for decades. With the internet, keywords are the primary tool search engines and databases (like Scopus or PubMed) use to index and retrieve articles relevant to a user’s search query. More importantly, they are used in databases for information retrieval and organization. In a sense, they function like social media hashtags, albeit less effectively.

Increased Citations: Keywords can make or break a paper’s chance of being cited. Judiciously selected keywords are correlated with higher citations counts. Higher visibility naturally raises the chances that other researchers will read and reference the manuscript. Citations are often used as a measure of scientific productivity. A series of studies published in 2009 and 2010 confirmed that the most influential factor affecting ranking in search results is citation count. Even though Google scholar has a unique citation-based ranking system called the h5-index, that does not rely directly on keywords, keywords are needed in the first place to boost visibly. The heavy influence of citations on ranking in Google Scholar means that certain groups, such as women and early-career researchers, are systematically disadvantaged.

Efficient Peer Review and Acceptance: Journal editors might use the keywords to classify a manuscript and to locate and assign it to appropriate peer reviewers which can help prevent immediate out-of-scope rejection.

Archival System: Keywords act as a type of searchable archival system—not unlike social media hashtags. They can help categorize research within a field and ensure it remains accessible for future generations of scholars. However, since keywords are user defined, how are these being efficiently curated? Some major databases (from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) such as MEDLINE/PubMed), will use a “controlled vocabulary” of standardized, pre-defined sets of terms used to categorize articles uniformly. If an author provides “skin cancer,” the system will substitute in their term- “Skin Neoplasms”.

Analysis of keywords themselves and the frequency of their appearances has been studied to figure out “research hotspots” in different academic disciplines and elucidate research and knowledge structures in current research.

For example, Gong et al. (2021) analyzed keywords in 8,281 articles published between 2009 and 2018 from Web of Science to examine changes in PhD research topics. Since 2009, PhD research shifted from being medicine-centric to technology-centric to human-centric. Large clusters of keywords indicate increased focus on developing knowledge resources and allocating scarce resources. The keyword related to the field of computer science demonstrate that artificial intelligence has been a major focus of recent PhDs.

Should your most important keywords appear in your title and abstract?

There is generally confusion among academics regarding how titles, abstracts, headings, and keywords influence the ranking and searchability of academic papers, leading to widespread conjecture and uncertainty about the process. Exhausted after completing a manuscript, many authors resort to selecting a few generic keywords without much strategic consideration.

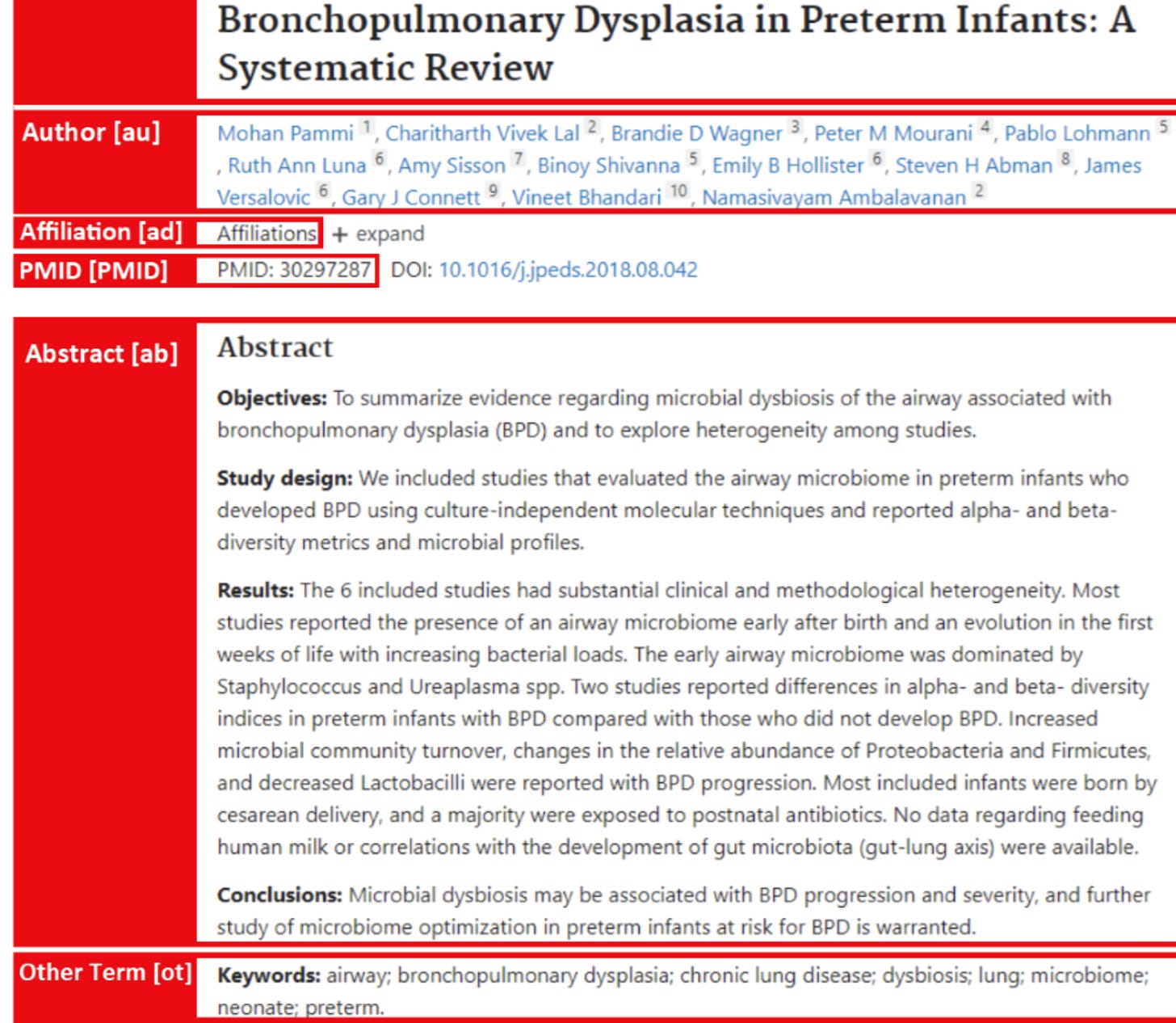

Example Pubmed paper layout with a list of keywords, and title and abstract that contain such keywords.

Research suggests that authors may be incentivized to choose keywords that already generate high search traffic. Conversely, older or less current terms (“global warming” instead of “climate change”) may reduce a paper’s visibility in modern databases and search engines.

Many search engine only scan an article’s Title, Abstract, and Keyword list. However, titles and abstracts have very limited wordcount that make it harder to ‘sprinkle in’ keywords. Thus, automatic keyword extraction (based only on title/abstract) misses a lot. Only about half of the author-provided keywords show up in the title/abstract, but almost half don’t:

Notably, Google Scholar scans the full text of an article, and does not use keyword indexing

Scopus/Web of Science does use do index author-provided keywords and also generate “index terms” or “keywords plus” algorithmically.

PubMed ignores author keywords but assigns MeSH terms through human/automatic indexing.

Automated Indexing, an Imperfect System

Let’s examine PubMed, one of the world’s largest biomedical databases. PubMed does not use author-assigned keywords but instead assigns MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms through a combination of human and automated indexing. While human indexers monitor quality, the final indexing and search results are largely controlled by algorithms — specifically neural networks. PubMed states that

Thus, the algorithm’s decisions are shaped by this relatively narrow 15-year span of publications. Many of these search algorithms are skewed to articles in English or papers in the Global North. Often, terms in the title are given greater weight than those found in the full text.

In the 1960s, Eugene Garfield’s Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) introduced the first citation index for academic journal publications: the Science Citation Index (SCI). This was later followed by the Social Sciences Citation Index and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index. The first automated citation indexing system was initiated by CiteSeer in 1997. SCI can both identify the publications of individual researchers, and track where and how often those publications are cited.

Web of Science, now part of SCI, allows for automated indexing and rapid retrieval of citation data. Today, as all searches are conducted online, automated indexing in electronic search systems is essential for journals to ensure visibility, discoverability, and integration into citation metrics. Hence, certain terms in the title, abstract, and “keywords” can improve searchability especially in databases that do not scan entire document text (Scopus, Web of Science).

However, abstracts are typically limited to 250 words which have been found to be overly restrictive in limiting searchability. Furthermore, stuffing keywords into titles can make them excessively long titles (>20 words) which can limit searchability and appeal to the reader. Often, the author is given little guidance on keyword selection, resulting in keywords that may be too broad or narrow for searchability.

Key Keyword Strategies for journal authors

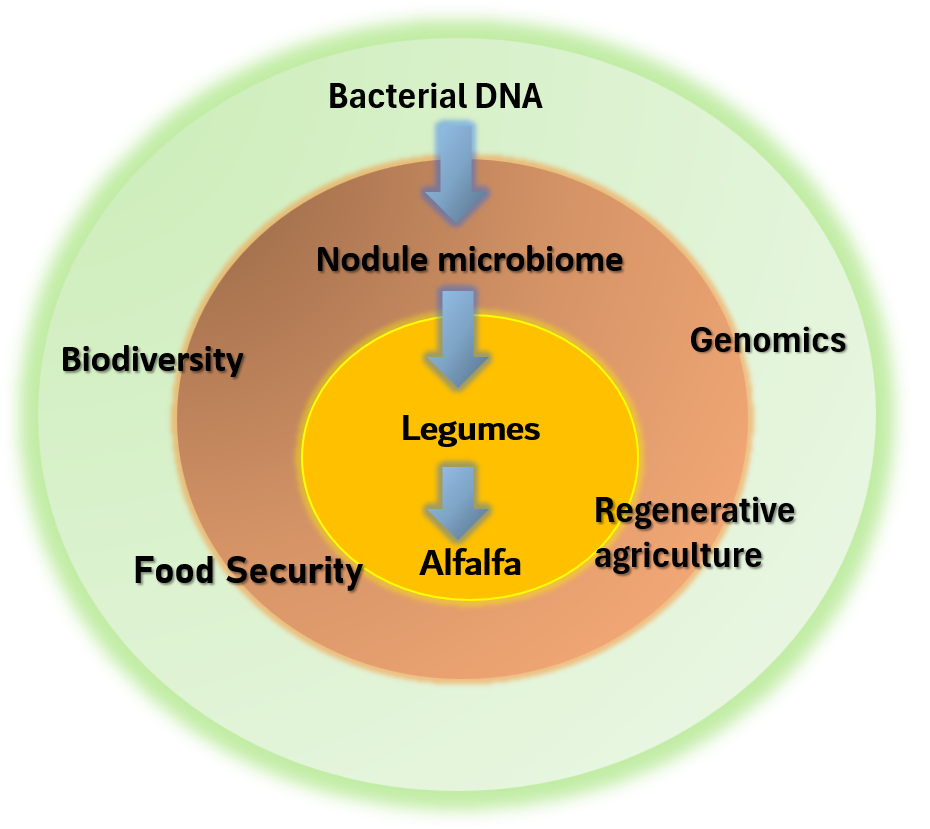

A demonstration of potential keywords for an academic manuscript: effective keyword selection should include both generic and specific terms (inner circles) as well as “implication” terms, such as food security, which can attract a broader audience as well as specialists. The challenge lies in reducing your paper’s complex content to just 6 or 7 well-chosen keywords

Think about the main topics and concepts of your research. What words capture the broad implications of your work (food security), the narrow implications (nitrogen fixation), and the species/subject (alfalfa).

Use a mix of broad and specialist terms. A word that is too generic like “microbiome” might drown you out, but a narrow word like “Rhizobia” might only appeal to specialist audiences.

Judiciously place your keywords in key areas such as the title, abstract, and headings. However, ensure they are integrated naturally (like 3-6 times) to maintain the readability of your manuscript. Words in the title are given the most weight in search engines, the earlier words weighing more. The first lines of an abstract are weighted the most in search engines.

Use headings and subheadings effectively incorporate keywords: Use relevant keywords in your headings where appropriate.

Engage with social media use keywords: When posting, include keywords and hashtags that are relevant to your research.

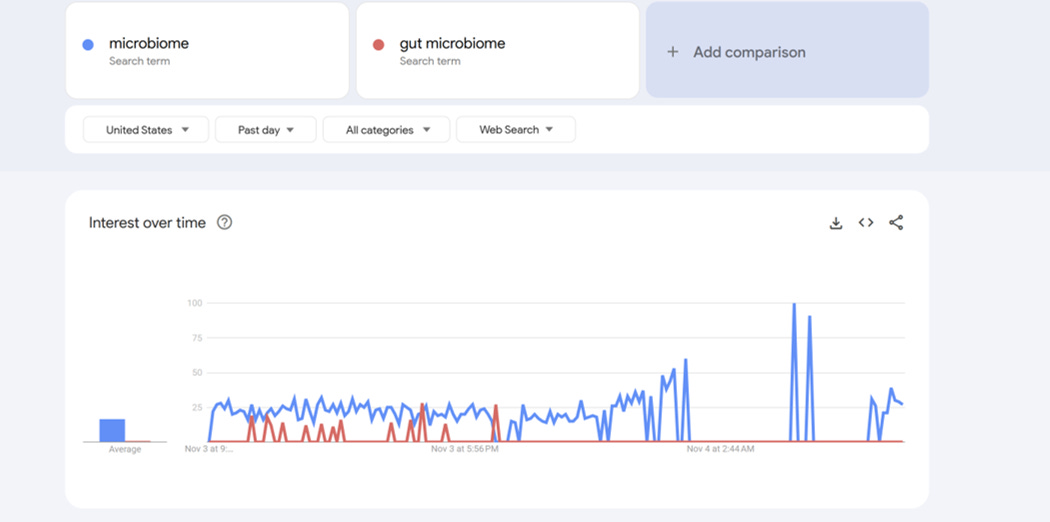

Tools like Google Trends, Google Ngram viewer, or academic databases can help you identify keywords in your field:

Google Trends Trends allows you to compare the popularity of broad versus specific keywords, such as the generic term “microbiome” versus the more specific term “gut microbiome.” While the broader term “microbiome” generates more overall interest over time, the more specific term “gut microbiome” connotes content related to health, diet, and wellness products and might be more relevant to audiences with health-related search intent for microbiome.

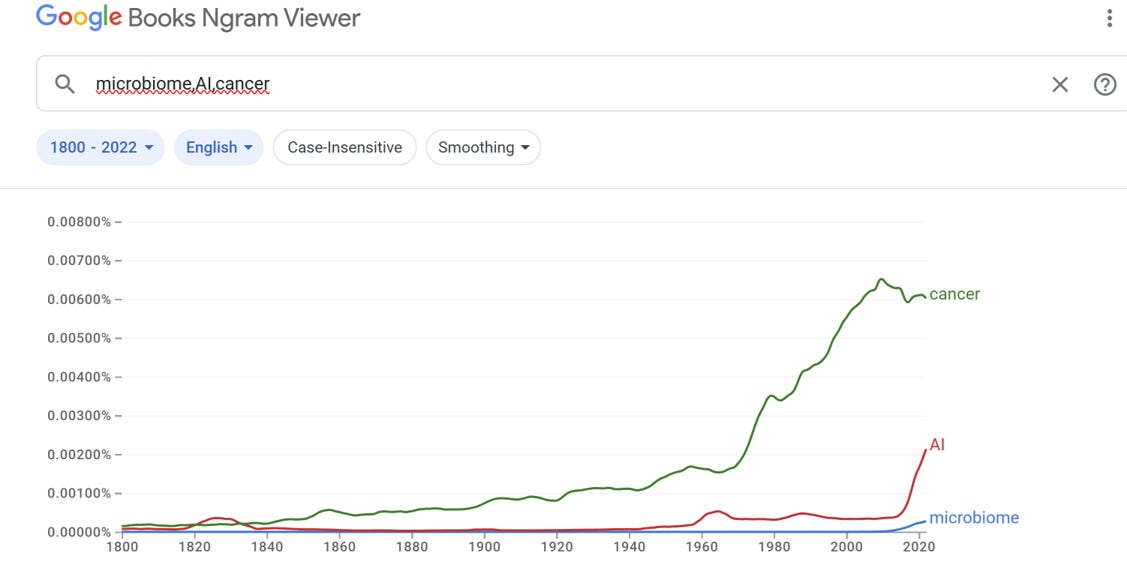

Google Ngram viewer allows you to see trends of word popularity over time. However, if a word is more popular it might be more generic, and your paper risks being ‘drowned’ out.

Conclusion:

Keywords truly dictate the science we see, for better for or for worse:

Poor, vague, or inconsistent keyword selection can significantly limit a paper’s reach, and the lack of guidance on effective keyword choice can particularly disadvantage early-career researchers with already low citation counts.

Keywords are especially important in databases that rely primarily on title and abstract scanning rather than full-text indexing.

However, full-texting scanning systems like Google Scholar are flawed, by their overreliance on citation count, which stem from keyword selection.

To maximize discoverability, some advise that keywords should be sprinkled into titles, abstracts, and headings, though whether broader or more specific terms are better is up for debate.

Beyond searchability, well-chosen keywords also aid peer review assignment, archival retrieval, and analysis of research trends.

In the high-stakes game of publish or perish, keywords function as a flawed yet essential ‘tagging’ system.

Next, I will take on social media hashtags!!

Very interesting, I did not give it so much thought before. I should do a bit of research so see how this is shaped in astroparticle physics

This really highlights a structural issue in academic publishing that often goes unnnoticed. The idea that keywords function like social media hashtags but less effctively resonates. Particularly interesting is the point about automated indexing systems like PubMed being trained on a 15year window, which inherently biases toward recent terminology and Gobal North perspectives. The tension between making titles searchable versus readable is something I hadn't considerd before.