Toxic Algorithms: ELO Rating & Dating Apps

And I've never been on a dating app.

Computer-based “dating services” started in the 1960s. Vintage computer ad Image.

What worries me now is that most people don’t have the time to develop a sense of self before they start to be controlled by the algorithms.’ Atlanta, Ellen. Pixel Flesh p. 195

Full disclaimer here, I have never used dating apps. However, I do have a strong interest in AI development, algorithms, feminism, and science and thought I’d investigate dating apps. My previous articles track how technology has become progressively “cooler” and more “friendly” for users; the advent of “computer dating” fits neatly into this narrative.

Before Computer Dating Was Cool

A relative of mine (born in the 1970s) was an early adopter of personal computing. Around 1998, he started using the Internet as a means to find a romantic partner. This was highly novel and only something you saw in movies like You’ve Got Mail (1998). He frequented chatrooms and indeed met his current wife (they lived happily ever after) and arranged a date. This was a really unusual dating strategy and garnered a lot of questions. People who knew him though, weren’t shocked. Of course, he couldn’t find a date in “real life”. He was “nerd” who needed a computer to help him find a date.

Computer dating services started in the 1960s and evolved to primitive chat rooms or connections via phone, video, or photo by the 1980s. However, they were not very well-received by some and had little “filtering” capability and sparked complaints from users: “No doubt about it. There are people on the network who are plain crazy," says Pam Dunn, alias Zebra3, of New York City. "Someone will talk to you on the private line, and you'll be having a great conversation. You're chatting for 15 minutes, then all of sudden they may ask for something really obscene."

80s dating service commercial.

Popular dating sites like eHarmony launched around 2000. By 2006, there was still distrust of Internet dating, concerns revolving around user safety, or deception from potential partners. However, a 2006 Pew survey revealed that Americans who used online dating believed it increased their potential pool of partners. This survey also revealed that over 60% of Americans had met their partner through work, school, or friends and only 3% through online dating. Online dating seemed to appeal to younger men, rather than to women according to that survey. Interestingly, the potential for violence against women also was a forefront concern.

By 2012, online dating had not yet gone mainstream. While it had become more popular, with dozens on online dating services available (over 25% of Americans now met their partners online) it was not quite “cool”. Early dating services mainly relied on similarities among answers to questionnaires. Often, they offered very lengthy (400+ questions) questionaries, and basically just matched people based on similar percent matching.

In the early 2010s, machine learning (non-generative AI) was incorporated into dating sites to better predict a user’s characteristics. However, the systems still struggled to make predictions of who people would like.

Making Computer Dating Cool, Via the App

Vintage computer dating ad (1985). Apparently, computer dating will feel like a light beam!

Withe the development of the smart phone and touch screens, dating sites could develop “apps” that were easy to use. Dating could now be easily accessed by a “cool” technology. Dating sites began to ditch the lengthy questionaries and just used “collaborative filtering” in which people provided basic info and swipe on who they like. They developed appealing, easy to use interfaces, which could be downloaded as apps. There were messaging features. There were glossy ads, promising glamourous romance. “Computer dating” was no longer for nerds but was mainstream.

Of course, the best way to be “cool” was to have a young audience, that is college students. Dating apps aggressively targeted college students, often partnering with fraternities and sororities and sending reps to infiltrate campuses and hook users. Dating thus, becomes a game. If you swipe so many times, you will find a match. It was like “shopping” a mentality that appealed to many:

These apps became an addictive game: the more you engage the more you could be rewarded.

How the Elo Rating System Creates a Hierarchy

To “hook” users, apps added gamification elements. Gamification provides users incentives to keep engaging with the apps. The Elo rating system is a common algorithm that has been integrated into the dating apps to rank user desirability. The Elo rating system, originally designed for chess rankings and now commonly used in sports betting, assigns players a score based on their past performance and the skill levels of their opponent. It uses pairwise comparisons (player A v. player B) to rank players. Rankings are based on previous wins and losses. The Elo Rating System is Zero-sum. That is a player’s probability of winning will decrease if another’s increases. The system is self-correcting in that it is better at predicting outcomes than other static models like regression which do not change or adapt once they are developed and trained. Self-correction is a key aspect to improving LLMs and AI. The Elo Rating System also being integrated into AI systems, particularly for reinforcement learning. (The Elo Rating System was notoriously used by Mark Zuckerberg’s FaceMash in which Harvard shut down its Internet due to high traffic.)

A user’s rating is hence calculated like this:

New Rating = Old Rating + k x (Actual Score - Expected Score)

k: A constant factor also known as a coefficient. In modeling, determining coefficients can be tricky, and a primary source of bias in models. For example, in chess the k value is 32 for experienced players, and 16 for new players. For other applications, determining a number for this could require a lot of research and would be key in the model development process.

Actual Score - Expected Score: This is where the rating will dynamically adjust itself based on the player’s current score, and the expected score that the player was predicted to achieve based on their rating and the opponent's rating. If a player consistently performs well, their expected score will increase. If a player consistently performs poorly, their expected score will decrease.

Expected score = 1 / (1 + 10^((Rb - Ra)/400))

Ra = player A’s rating, and Rb = player B’s rating. Expected score is between 0 and 1 and reflects the probability of winning against an opponent. The stronger player will have a higher Expected Score.

The limits of this model are that player/users are not always consistent; a bad day, illness, ect. can throw off scores. It doesn’t account for random factors or events.

Once someone dominates the rankings, it is harder in the Elo system to knock their score down so to speak. A hierarchy develops. Other players remain at consistently lower probabilities of winning and thus lower rankings. It’s harder to improve ratings. This may be fine in sports tournaments where there can only be one winner. But in dating apps/social media, the hierarchy that the Elo Rating system engenders can be extremely problematic.

A male investigative reporter with FastCompany in 2016 interviewed Tinder CEO Sean Rad who confirmed the scoring system. Rad told the reporter that his Elo score was “above average,” but stressed “that the rating is technically not a measure of attractiveness, but a measure of “desirability,” in part because it’s not determined simply by your profile photo. “It’s not just how many people swipe right on you,” Rad explains. “It’s very complicated. It took us two and a half months just to build the algorithm because a lot of factors go into it.””

The ELO Rating system as integrated into these apps reinforces problematic aspects of beauty culture, including “Instagram face” and racial biases towards white women. These become echo chambers in which women are rewarded (their rating rises) for adhering to beauty standards and rendered invisible (lower rating, less visibility) if they do not. And the implied consequence of not conforming, in the context of these apps, is that your rating will fall and you will not receive love.

Moving Past ELO: Generative AI in Dating Apps

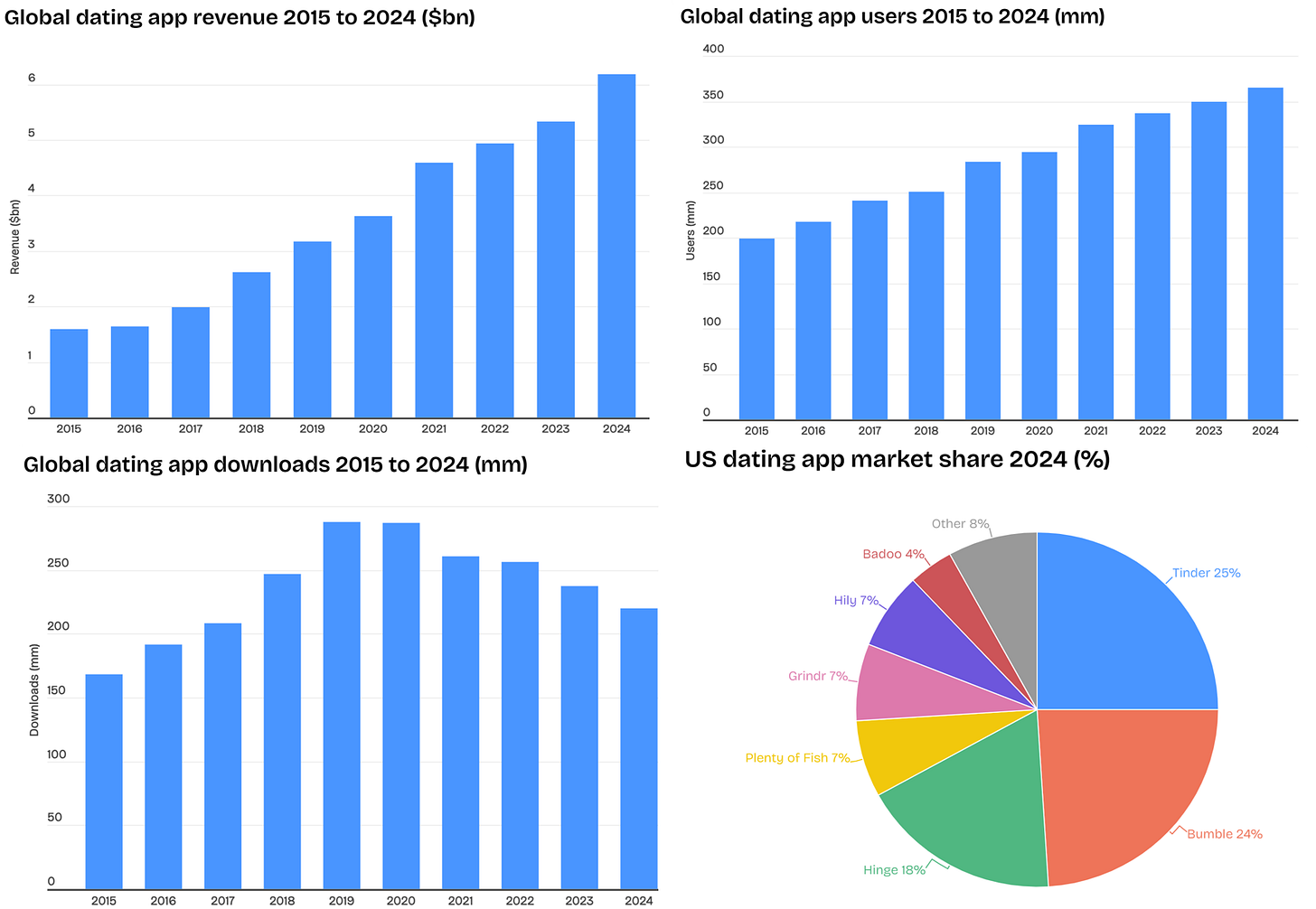

The ELO rating system has received criticism for its popular integration into many dating apps, and Tinder now claims to use a different ranking algorithm. Currently, dating apps are losing their enchantment, though they aren’t going anywhere ($6.18 billion revenue in 2024). New users on dating apps are stagnating, and downloads are decreasing; these companies need new, innovative methods to lure more people in. Non-generative AI methods like machine learning have been integrated into programs since the 2010s. As the number of users are stagnating on dating apps, AI is moving to the forefront. Apps are now integrating generative AI and Natural Language processing into their programs to improve matches.

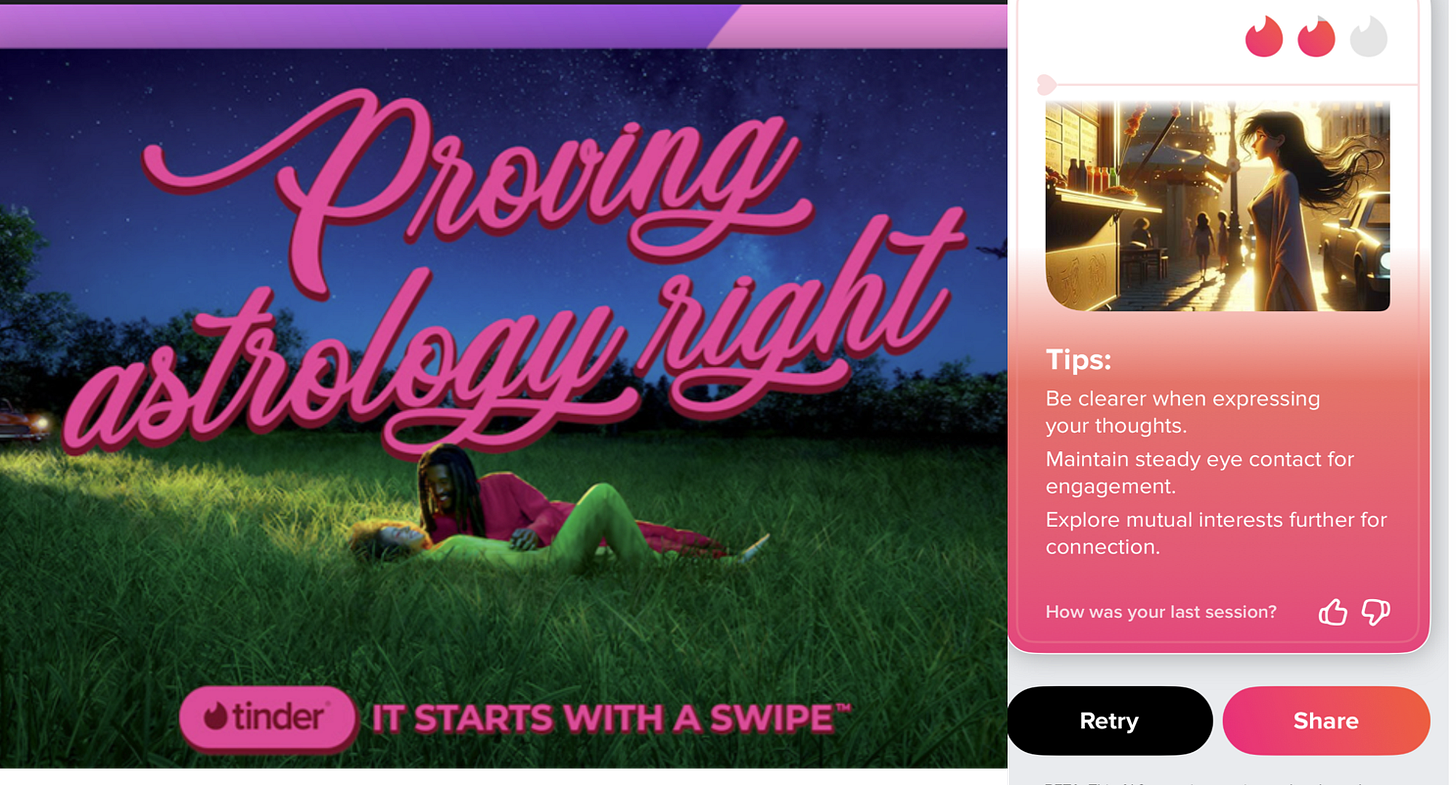

LEFT: 2023 Tinder ad. RIGHT: 2025 Tinder “flirtbot?”

Natural Language processing could actually be used for good to filter out fake users. However, is it? Seemingly, it’s being used to read users’ personal messages to better find people with similar communication styles'. More disturbingly is the introduction of “chatbots” to presumably aide users on how to be “flirty”. These “fake” users may be used to lure users to continue engaging with the app. The computer has replaced other ways of meeting romantic interests, with roughly 50% of couples meeting online and at least 30% of Americans adults are using dating apps. However, only half of users have said that their experience with dating apps has been positive.

Other Dangerous Aspects of AI apps:

Obtaining user locations. Not only are the apps tracking the user and collecting data on the location, dating app companies have leaked users’ location data.

Dating apps can facilitate abuse and harassment. Initial concerns of the dangers of dating apps (stemming back to the 1980s) have never been adequately addressed.

Promoting a culture of surveillance and tracking of users. These apps gain your face through pictures and geographic information. Given Big Tech’s poor record of data privacy, users should be concerned what it will do with this collection of people’s faces and information.

Stigmatizing singledom. Psychologist Bella DePaulo argues that single people may fair worse in the consideration of medical care and treatment; they may be socially isolated or ostracized because of their unwillingness to conform to the “norm” of marriage. Feelings of loneliness and unworthiness can be exacerbated through the glamorization of dating via social media and dating apps.

Conclusion

This wonderful quote from an amazing book I’m reading now called Pixel Flesh by Ellen Atlanta:

A positive view of our digital culture would lead us to believe that we have the ability to freely shape our self-presentation online, that away from the shackles of traditional media, we can create a utopia in which inclusivity, diversity and individuality are paramount. But the data suggests otherwise. Our digital worlds are creating an ever-restrictive regime of beauty ideals, predicated by a narrow set of desirable features and facial characteristics that can be obtained by any woman if she makes the ‘right’ consumer choices (p 21).

And no, you won’t find me on a dating app any time soon.